On this significant Juneteenth remembrance, the Carnegie Center for Art and History is pleased to announce the commission of a new addition to the permanent collection. Thanks to an anonymous donor, a small 13 inch, bronze casting of the maquette of Ed Hamilton’s large-scale sculpture Spirit of Freedom is currently in production at Louisville’s Falls Art Foundry, anticipated to be completed in the coming weeks.

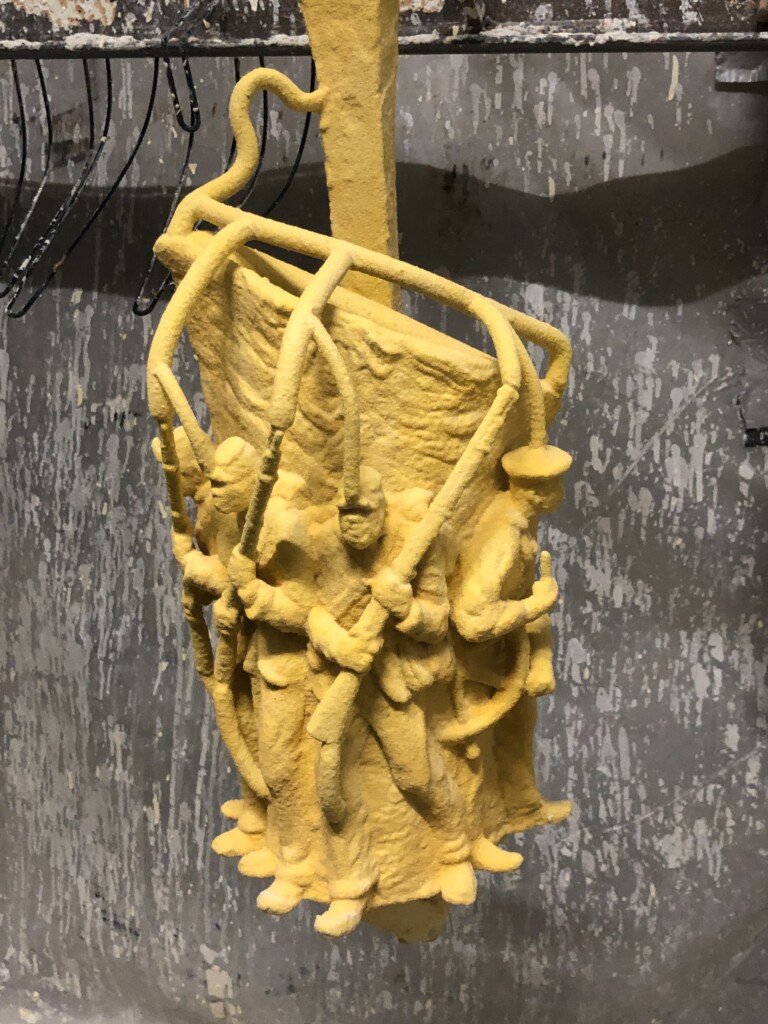

Ed Hamilton, Spirit of Freedom, limited edition 13 inch maquette, bronze casting in process, wax being coated with ceramic shell, 2020

Ed Hamilton, Spirit of Freedom maquette, 13 inches

This is the 155th anniversary of Juneteenth—the day in Texas in the year 1865 when the last enslaved individuals learned that the Emancipation Proclamation had truly happened two years earlier and that they were finally and indeed free! This day has become recognized as the African American Fourth of July representing true freedom from slavery. Amazingly, that is how human chattel ended in our country after being practiced on American soil since the year 1619.

Civil War battles may have ended long ago, but the healing and reconstruction have never fully happened. As we have seen, our national landscape is also dotted with monuments to a misplaced past that can impede the healing process. On rare occasions, we remember the right things. With perseverance and luck, knowledge and history get to shine through, and culture moves forward. We now seem to be in a period in deep need of reconciling the past before moving forward with all the other challenges facing a contemporary society.

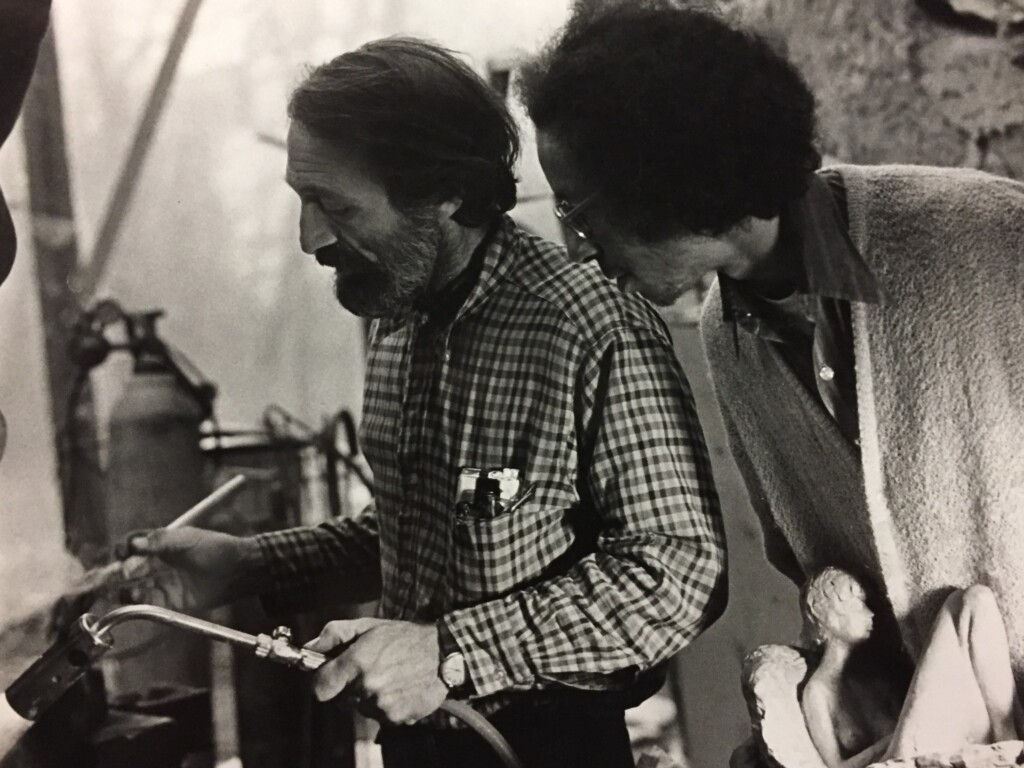

Barney Bright and Ed Hamilton, 1973

Louisville-based artist Ed Hamilton was the second of Barney Bright’s talented assistants that worked and learned from him in the old studio and foundry on Louisville’s Frankfort Avenue. The two artists are an interesting contrast. While Bright’s reputation has remained mostly local, Hamilton has created and continues a career of national importance. There are too few public artworks honoring the African American experience, but many of the important ones have been created by Ed Hamilton. For a fuller look at Hamilton’s remarkable career as an artist and visual historian, you may enjoy this fascinating short video by Joanna Hay Productions. Ed Hamilton: The Power of Bronze

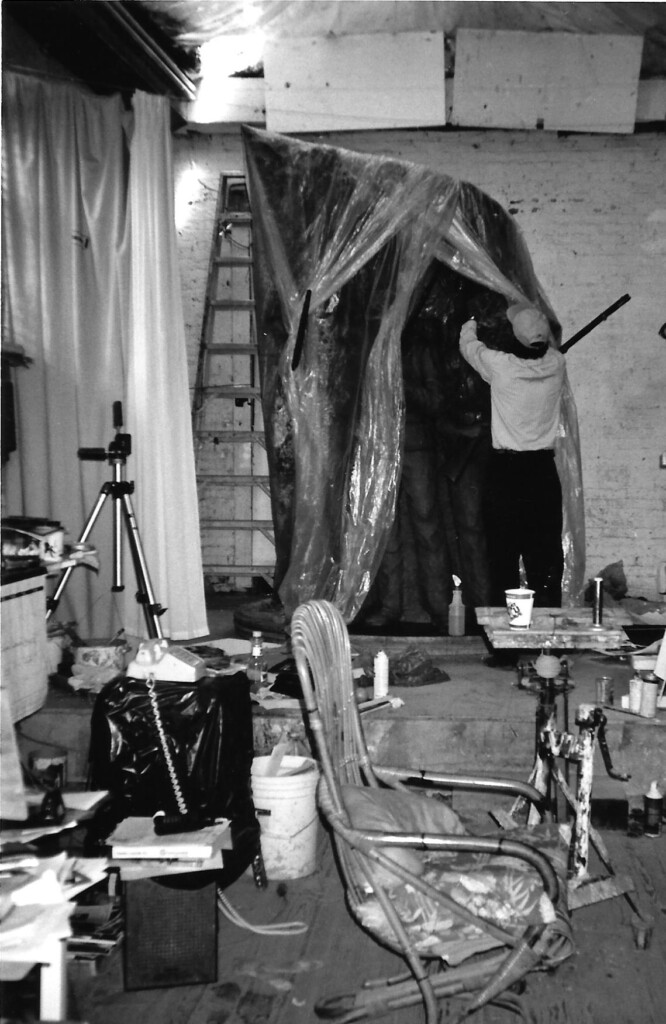

Ed Hamilton in his studio with Spirit of Freedom

Dedicated on July 18, 1998, Hamilton’s Spirit of Freedom is one of his most important commissions and is the centerpiece of the African American Civil War Memorial located in Washington, D.C. The Carnegie’s sculpture will be a limited edition casting of the small maquette, or model, of the full-scale memorial. This memorial is the first to honor all the names of the United States Colored Troops and their gallantry and sacrifices. As Frederick Douglas once said, “Who would be free themselves must strike the blow. Better even to die free than live slaves.” President Lincoln was depending on men newly freed from bondage to swell the Union’s ranks. It is estimated that ten percent of the Union army and navy were made up by troops of color. The memorial records on two curved walls, the names of more than 200,000 men who were members of the USCT including the 7,000 white men that served along with them.

Hamilton’s bronze centerpiece is 12 feet tall and presents as a double-sided, curved wall. The forward-facing side of the monument has four larger than life-sized soldiers—three authentically detailed infantry men of different ages with packs and rifles, along with a midshipman with his hands on the wheel of a naval vessel. They emerge from and stand in front of a stylized waving flag that includes in low relief, a face with closed eyes, and crossed hands that add a benevolent spiritual element floating high above the soldiers.

Spirit of Freedom clay model detail, Ed Hamilton, 1998

The opposite or convex side of the sculpture is the reason why men enlisted into the United States Colored Troops. In low relief, Hamilton created a goodbye scene. A young African American soldier bids farewell to his extended family before going off to war. If the country were to ever live up to its promise and reward, than all the risks needed to be shared. I will long remember my visit to Ed’s studio to get the tour and watch as he carefully unwrapped the plastic from the still wet clay models and explain how he imagined each figure and their back stories.

Descendants of the USCT from all over the country attended the 1998 dedication of Hamilton’s sculpture at the nation’s capital, including several bus tours from Kentucky and Indiana. The unveiling and celebration of the Spirit of Freedom helps to rectify a historical injustice—in 1865, the Grand Review of the Army paraded in celebration of the Union victory, but the USCT were excluded from the festivities. The African American Civil War Memorial and Spirit of Freedom sits on a triangular plot of land in a community that had been identified in the 1870’s as an appropriate site for a national USCT memorial. It only took 128 years to fix this wrong in a city filled with iconic memorials.

Al Gorman

Coordinator of Public Programs and Engagement

Carnegie Center for Art and History

A Branch of the Floyd County Library